The Philippines, an archipelago of over 7,000 islands, is part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, making it home to numerous volcanoes and mountain ranges that lead down to the a coastline that is among the longest in the world, featuring white-sand beaches, dramatic cliffs, and coral reefs.

So you can imagine, with all that fire and water and island sun what a magnificent bounty of gifts from the land and sea have been available to weave into a cuisine. There is the Banaue Rice Terraces a 2,000-year-old UNESCO World Heritage Site, often called the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” And the Bukidnon Plateau, known as the “Food Basket of Mindanao,” filled with pineapple farms and rolling hills. There is the Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park, another UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the best diving spots in the world, teaming with marine life.

Embarking on a journey through the Philippines’ authentic dishes is like exploring a map in 4d, living in it with the people.

But first, a Short History of the Philippines

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Philippines was home to numerous ethnolinguistic groups with advanced societies engaged in agriculture, trade, and maritime activities. Various indigenous groups, such as the Tagalogs, Visayans, and Igorots, established thriving communities. The islands had trade connections with China, India, and the Arab world as early as the 9th century, bringing influences in language, religion, and culture. Islam was introduced in the 14th century, particularly in Mindanao and Sulu.

Spanish Colonization (1521–1898)

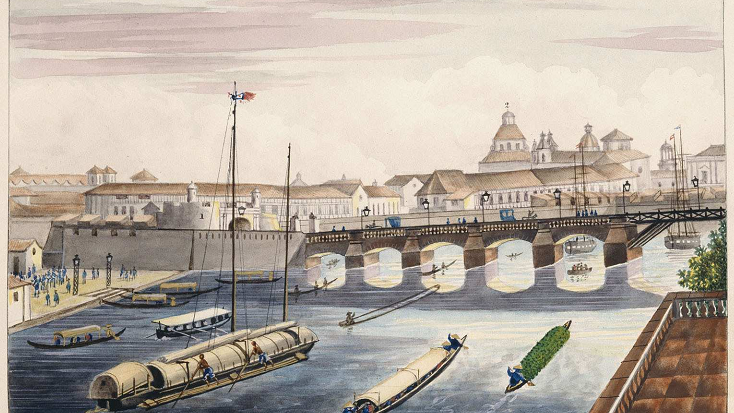

Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in 1521 under the Spanish crown, marking the beginning of over 300 years of Spanish rule. Although Magellan was killed in the Battle of Mactan by the warrior Lapu-Lapu, Spain continued its conquest, formally colonizing the islands in 1565 under Miguel López de Legazpi. Manila became the colonial capital in 1571.

The Spanish brought Christianity, which remains a dominant religion today, and established a feudal system where Spanish elites (the peninsulares and insulares) ruled over indigenous Filipinos (indios). The Spanish also introduced the galleon trade, which connected Manila to Mexico and Spain, making the Philippines an important hub of global commerce.

Revolution and American Rule (1898–1946)

Inspired by Enlightenment ideals and the writings of Filipino nationalists like José Rizal and Andrés Bonifacio, Filipinos began revolting against Spanish rule in 1896. The Philippine Revolution led to Spain’s defeat in 1898, but instead of granting full independence, the United States took control after winning the Spanish-American War.

The Philippine-American War (1899–1902) followed, as Filipinos resisted American occupation. The U.S. established schools, infrastructure, and a new government system, but the Filipinos continued their push for self-rule. A Filipino/American food exchange began that would continue through the second world war – accounting for surprising Filipino-inspired dishes on the table in white American kitchens.

World War II and Independence (1946)

During World War II (1941–1945), Japan invaded the Philippines, leading to a brutal occupation and significant destruction, especially in Manila, which suffered one of the worst urban battles of the war. The U.S. and Filipino forces, led by General Douglas MacArthur, liberated the country in 1945.

On July 4, 1946, the Philippines finally gained full independence from the United States, establishing the Third Republic.

Post-War to Modern Era

In the post-war years, the Philippines saw economic growth but also political turmoil. The Martial Law era (1972–1986) under Ferdinand Marcos was marked by human rights abuses and economic struggles, leading to the People Power Revolution (1986), which peacefully ousted Marcos and restored democracy under Corazon Aquino.

Today this vibrantly green collection of peaks and valleys rising out of the sea is known for its diverse culture, resilient people, deep historical roots, and of course, delicious food.

So what are the dishes that encapsulate this dynamic legacy of Southeast Asian-Spanish-American cultural smash-up? I’m so glad you asked.

Start Here: Adobo

The Quintessential Filipino Stew

Adobo is often hailed as the unofficial national dish of the Philippines, embodying the country’s knack for harmoniously blending flavors. At its core, adobo is a savory stew that marries meat—commonly chicken, pork, or a combination thereof—with vinegar, soy sauce, garlic, bay leaves, and black peppercorns. The result is a dish that’s simultaneously tangy, salty, and aromatic.

The term “adobo” is derived from the Spanish word adobar, meaning “to marinate,” but the cooking method predates Spanish colonization. This cooking technique involved marinating and simmering meat in vinegar, which not only enhanced flavor but also acted as a natural preservative. Garlic, bay leaves, and black peppercorns were later added, creating the foundation of what we now know as Filipino adobo.

Historians believe that early Filipinos developed this preservation method independently of any foreign influence. When the Spanish colonizers arrived in the Philippines in the late 16th century, they encountered this native cooking method. Spanish adobo is entirely different—it refers to a vinegar-based marinade used for meats, but it is not a dish itself – the Spanish then remove their protein from the paprika-heavy marinade and braise it separately.

Each region adds its own twist: the Visayas use turmeric in adobo sa dilaw, while Bicolanos enrich theirs with coconut milk. Adobo’s versatility and simplicity have cemented its place in Filipino households across generations.

Where to Savor Authentic Adobo

Manam Comfort Filipino: Manam offers a contemporary take on Filipino classics, including their well-loved adobo dishes. Their menu caters to both traditionalists and those seeking modern interpretations.

2. Sinigang

A Symphony of Sourness

Sinigang is a beloved Filipino soup known for its distinctive sour broth, typically derived from tamarind (sampalok), green mango, or other native sour fruits. This hearty dish often includes pork, shrimp, or fish, with vegetables like kangkong (water spinach), eggplant, and radish.

Sinigang reflects the Filipino palate’s deep love for sour flavors. Unlike other Southeast Asian cuisines that favor sweetness or spice, Filipinos relish the sharp tanginess that makes sinigang so comforting and uniquely theirs.

Where to Savor Authentic SinigangAbe’s Restaurant, Manila – Famous for Sinigang na Baboy sa Sampalok (pork sinigang with tamarind) and also a Sinigang with fish and fruity guava.

Check out Abe’s Farm and spa where you can stay in restored farmhouse buildings and indulge in local specialties.

3. Lechon

The Festive Centerpiece

Lechon, a whole roasted pig, is the crown jewel of Filipino celebrations. Slow-roasted over charcoal, it boasts irresistibly crispy skin and tender meat, making it the star of any feast.

The tradition of roasting pigs dates back to pre-colonial times and evolved under Spanish influence. In Cebu, lechon is an art form, with distinct seasoning techniques passed down through generations. The meat is always served with rice, various sauces, sometimes noodle dishes (for good luck), and atchara—a Filipino pickled papaya side dish with carrots, bell peppers, and raisins soaked in sweet-sour vinegar.

The most iconic pairing for lechon is lechon sauce, a thick, sweet-savory dip made from liver, breadcrumbs, vinegar, sugar, and spices. This sauce was popularized by the Aristocrat Restaurant in Manila and has become a staple at lechon feasts. Some regions (like Cebu) prefer to enjoy lechon without sauce, believing the seasoning is enough. Others use spicy vinegar dips instead.

Where to Savor Authentic Lechon

Rico’s Lechon, Cebu – Offers classic and spicy variations of Cebu’s famous lechon.

Pig Senyor , Manila – A crispy, crackly staple of the community.

4. Kare-Kare

A Nutty Ox and Offal Mix

Kare-kare is a rich stew known for its peanut-based sauce, typically featuring oxtail, tripe, and vegetables. It’s traditionally served with bagoong (fermented shrimp paste) to enhance its depth of flavor.

Believed to have roots in Pampanga, the culinary capital of the Philippines, kare-kare may also have been influenced by Indian curry introduced through trade routes. The dish’s labor-intensive preparation makes it a special-occasion staple, reinforcing family bonds.

Where to Savor Authentic Kare-Kare

Cafe Juanita, Pasig City – Known for its rich, creamy peanut sauce and tender meat.

5. Pancit

The Noodle Narrative

Pancit encompasses a variety of noodle dishes introduced by Chinese immigrants and adapted to Filipino tastes. Whether it’s stir-fried Pancit Canton, thin rice noodle Pancit Bihon, or saucy Pancit Malabon, each version reflects regional influences.

The name “pancit” originates from the Hokkien phrase “pian i sit,” meaning “something conveniently cooked.” Introduced by Chinese traders as early as the 10th century, noodles have since become a symbol of longevity and prosperity in Filipino celebrations.

Where to Savor Authentic Pancit

Amber Golden Chain, Manila – Famous for Pancit Malabon and Pancit Canton.

Forget Me Not Specialty Cakes – Order the Pancit Sotanghon – stir-fried sotanghon noodles topped with lechon flakes and crispy Bulacan longanisa. Yes, it is also a cake shop!

6. Halo-Halo

It’s Hot, How to Chill

Halo-halo, meaning “mix-mix” in Tagalog, is a vibrant dessert featuring crushed ice, evaporated milk, and a medley of ingredients like sweetened fruits, beans, gelatin, leche flan, and ube (purple yam).

Rooted in Japanese kakigōri (shaved ice desserts), halo-halo evolved in the Philippines with local ingredients. It’s more than just a treat; it’s a reflection of the country’s diverse influences and the Filipino penchant for blending contrasting flavors into perfect harmony. Ube flavored, purple-hued ice cream has recently taken the world by storm – you’ll notice it in fancy ice cream shops across the United States and Europe.

Where to Savor Authentic Halo-Halo

Razon’s of Guagua, Pampanga – Known for its minimalist yet delicious halo-halo with just three main ingredients: macapuno, sweetened bananas, and leche flan. But don’t worry – they have multiple varieties, including the ube-topped kinds.

7. Taho

A Morning Ritual

Taho is a warm, comforting snack made from silken tofu, arnibal (sweet caramel syrup), and sago pearls. Street vendors serve it fresh in the morning, calling out “Tahooo!” as they roam neighborhoods.

Taho traces its origins to early Chinese immigrants who brought the art of making silken tofu. Over time, Filipinos sweetened it with arnibal and sago, turning it into a beloved breakfast staple.

Served in a simple plastic cup, taho is meant to be enjoyed warm and fresh, its layers of soft, pudding-like tofu melting into the syrup’s sweetness while the pearls add a playful chew.

Though traditionally plain, regional variations exist—Baguio’s Strawberry Taho swaps arnibal for a fruity twist, while some cities experiment with chocolate or ube flavors. But at its heart, taho remains a simple, comforting, and deeply Filipino experience, embodying the warmth and hospitality of the country in every spoonful.

Where to Savor Authentic Taho

Street Vendors in Baguio City – The cold mountain air makes Strawberry Taho a must-try local delicacy.

For more travel tips and foodie experiences, check out CercaTravel.com.